We went to Panama for spring break. Jo planned a lovely trip – a few days in Panama City and around both ends of the canal, a few at a beach on the Pacific coast, and then in a town nestled inside the caldera of an extinct volcano.

The main part of Panama City is modern and bustling with high rises and snarly traffic but it is surprisingly easy to drive around in. The part of the city we fell in love with is Casco Viejo – the old quarter. The funny thing about the old town is that it is the new old town. The OG old town was already a 150 years old in 1671 when the Governor ordered it burned down so that there would be nothing left to pillage by Henry Morgan, the pirate who later became the Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica (and a plantation owner and namesake of Captain Morgan’s, the rum). In 1673 the town was rebuilt with better defenses at the current location of Casco Viejo. More recently, it has been reborn again as a gentrified posh tourist area with nice hotels and restaurants, beautiful churches, and lovely old apartments.

And then there’s the canal. There are tales of international intrigue, medical science, and engineering in its origin story. Not too briefly (you know me), the French, under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps, fresh from his success at the Suez canal which opened in 1869, took the first crack at building a canal across Panama in 1881. The Suez is a sea level canal that was excavated through mostly sand. Panama is neither sandy nor flat. By 1889, de Lesseps was done and bankrupt and over 20,000 people had died during construction of a half completed ditch. The main cause of death: malaria and yellow fever. Even as recently as 150 years ago, these diseases were attributed to “miasma” or foul air. The Americans saw their opportunity. Over the next 15 years the US engineered the independence of Panama as a new rebel country from Colombia, bought rights to the canal zone in perpetuity from the newly independent country, bought the remains of the French construction and equipment, and paid Colombia off to recognize Panama’s independence. US engineers were apparently disembarking in Panama before it had even officially announced its independence. The planned American canal was to provide a much needed way to transport people, goods, and military supplies between the two coasts. Even pre-canal, the fastest and most comfortable way to travel from San Francisco to New York was two steamers on either side and a short trip on the Panama Railroad across the isthmus.

At about this time, a Cuban doctor, Finlay, hypothesized that if a mosquito bites a human with yellow fever, and then bites a healthy human, the healthy human gets “infected” with yellow fever. At last a disease vector! By draining swamps and using screened netting, the incidence of yellow fever in Havana dropped precipitously. Walter Reed and Gorgas, two American doctors, were quick to comprehend this new thinking and propel it further. Just a few years prior to this, in 1897, Ronald Ross in Secunderabad, now a neighborhood of my hometown of Hyderabad, had put it all together when he found the malaria parasite in the blood of infected humans and in the gut of infected mosquitoes, for which he got the Nobel prize in 1902. When Gorgas arrived in Panama armed with this new knowledge, it was one of the two reasons why the American Panama Canal succeeded where the earlier French attempt had failed.

The other reason was that the American chief engineer ditched the idea of de Lesseps’ sea level canal. The Chargas river was a part of the French problem – turning from a rocky, dry bed during the dry season into a torrential flood for most of the year. A few French engineers had broached the idea of an artificial lake and lifts on either side. In 1906, John Frank Stevens, the self-educated American chief engineer, successfully pitched the idea to Roosevelt. The idea is simple. Instead of digging a sea level canal through mountains, dam that Chagras. Use the artificial lake to flood the central part of the isthmus to 85 feet above sea level. Most of the 50 mile voyage between oceans would be over this lake. Build locks on either side to raise and lower ships up to the lake. Use gravity and the water from the lake to float the ships on their 85 foot uphill and downhill journeys. Stevens, his successor, and Grogas got the job done, along the way building the largest dam and largest artificial lake of their time. Still, over 5000 additional men died building the canal. It officially opened in 1914. For the next 100 years it remained practically unchanged. Ship builders made Panamax sized ships that are huge but can still pass safely through the locks.

The canal was handed over by the US to Panama on December 31 1999. This was the result of a treaty signed by Carter in 1977, and followed a worsening of relationships between Panama and the US. And in between, the US sent in troops in 1989 to end the dictatorship of Noriega. Other than that it appears that things have worked out well. Post-Noriega, Panama is a vibrant democracy – we were there during election season. The Panama Canal is very well run and in 2016 a new larger set of locks were added.

We visited the 110-year old Miraflores locks on the Pacific side and watched Lucky Gas, a liquified gas carrier, transit. The next day we went to the Atlantic side to the new Agua Clara locks and saw G. Paragon, a Neopanamax size ship, transit into the Atlantic. The voyage from ocean to ocean takes less than 12 hours and a Panamanian pilot takes over command of the ship during this time. Tolls average $50,000. Each transit requires about 50 million gallons of fresh lake water to be emptied into the oceans. The lake water is replenished by rains. Americans are one of the biggest water guzzlers on the planet. We use 100,000 gallons of water per home per year on the average. That is 500 homes’ entire annual water needs for one ship. Over 1,000 ships do this every month – when there is enough water. During the dry season, the canal authority decreases the number of crossings to conserve water. Wait times become longer. That thing you bought at Costco last Sunday takes longer and becomes more expensive to get here from China.

I thought it was all pretty amazing. The kids and Jo were impressed too. But for about 15 minutes. Then it’s just another fucking ship going through the fucking canal. After a couple of days of this we drove off about 6 hours due west (Panama is almost horizontally placed on the map – like a laying down shallow S with the Atlantic to its north and Pacific to the south). The roads were easy except for the extra patience I had to find. There were frequent cops checking for speeding and how I didn’t get pulled over half a dozen times I don’t know. The speed limit on a couple of toll highways is 110 km. Otherwise it is 90 km on most highways (that’s about 70 and 55 mph for the metric-disabled). If you are used to driving at 90 mph it feels like your life is passing you by. Except when your google maps is telling you where to turn next. Every road has at least six names on the map except the two you actually see on the physical signage. And google reads all of the names out in the most awful non-Spanish pronunciation you can imagine. So things get interesting at turns.

Once we left the main interamericana highway 1, the drive to our next destination reminded me of our trip to the Guanacaste region of Costa Rica – understandably because we’d be there if we had kept driving for another 500 miles. We got to our beach house and pool and lovely uncrowded bay where we hung out for the next few days. We slowed down and swam, walked, surfed, ate, and drank. There was a very good grocery store about a 10 minute walk away with pretty good wine and superb fresh pineapple. The restaurants were a five minute walk away. In the mornings or after dinner you could walk for an hour on the beach and perhaps see one other person with their dog. Evan and Vivian rented surfboards and Evan even got Vivian to take the boards out at 7:30am on the morning we were heading out to get a last bit of surfing in. Jo and I swam in the pool and a bit of the ocean and read and I worked on my computer (there is high bandwidth wifi everywhere on earth now : – ). This is the view from my poolside office. That’s Vivian, Evan and Jo on the other side sitting out in the sun.

In case we need to find this place again – it’s Playa Venao – I’ve dropped a pin.

Next stop – El Valle de Antón. This is small town tucked away inside the caldera of an extinct volcano. The numbers change somewhat between the different informational signs around town, but it has been extinct for at least 13,000 years. Perhaps as long as 56,000 years. We climb from the coastal plains into cloud forests and pass lovely small hamlets with volcanic rock churches and tiny street-side fondas advertising the day’s menu on chalkboards. And then we careen down precarious hairpin bends, aka switchbacks. We’re in a beautiful little town with manicured walkways and stately mansions. The trees are full of blooms, yesterday’s flowers cover the sidewalks. Coffee, fresh fruit, and pizza places abound, along with local sancocho restaurants. We are at a nice little hotel called the Golden Frog inn at the end of a street with amazing flowers. There’s a bonsai section with ancient looking bonsai bougainvillea. I learned next morning at breakfast that a tortilla in Panama is a fat little corn cake.

Vivian and I went zip lining one day. We swam as a natural pool, and I hiked up towards two of the peaks but never made it to either because of strong winds and a spot of rain but down in the town, the weather remained nice and temperate.

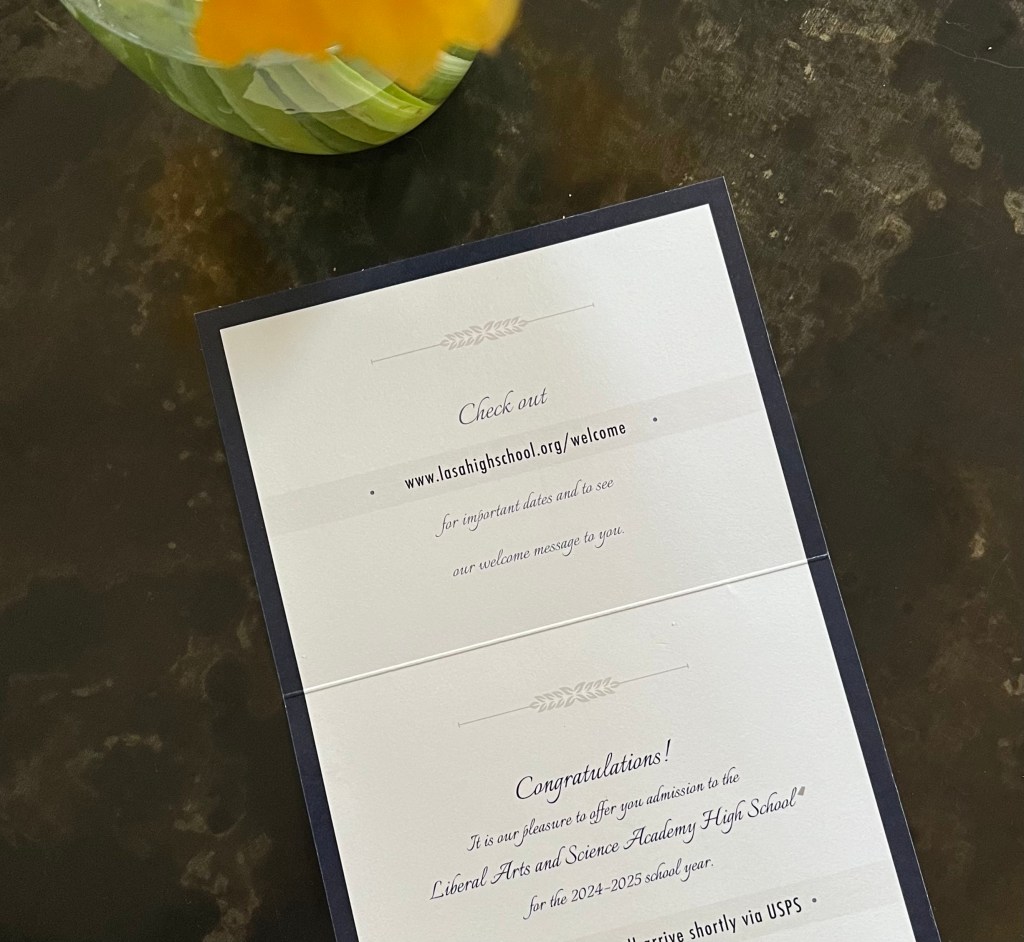

The trip was a little bit extra special because hours before we left home, Evan got his acceptance letter from LASA. When we got back from Panama, he officially said no thanks to St. Stephens, and decided to be a LASAraptor for high school. Yay to him though Vivian is slightly disappointed that her little bro won’t be at her high school for her senior year. Speaking of senior years coming up, Jo and I also realize that this may have been our last or second to last family spring break for a bit, assuming that college kids go off and do their own thing for their spring breaks. Wow – after 17 years of getting used to one thing, change is coming.